The design for the 36er is now well under way (

Initial idea,

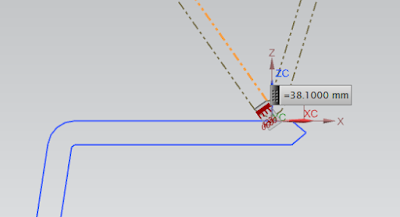

dual disc justification). The geometry is all but finalised (first draft anyway) for the entire project but it will need it to be checked and may be modified depending on the frame calculations and any wall thickness's that I wouldn't be able to obtain. Below the geometry for the bike can be found (On one midge bars would be used for this hence the really long effective top tube) and will involve quite a lot of bracing to get the frame strong enough to withstand all of the forces that are required in BS EN 13766. As you can see in order to get the chain stays (and the wheelbase) as short as possible a split in the seat tube would be required to provide clearance for the 3 foot diameter wheels. In another attempt to get the bike to handle reasonably and try to counteract the overly large wheels the trail value that has been selected (~85mm) is similar to that of a Trek Superfly in the smaller sizes, any less trail (i.e. any more fork offset) made me uncomfortable with the strength of the material selected for the fork stanchions. In Fig. 2 the trail relation to the head angle and the fork offset can be seen.

|

| Fig. 1 36er Geometry |

|

| Fig. 2 Trail relation to head angle and fork offset |

The calculations for the forks (in accordance with BS EN 14766:2005) have all been done. This includes a horizontal fore aft force of 600N followed by 1200N in a repeating cycle (1e5 cycles) in the configuration seen in Fig. 1 (this is actually a frame test but the forks can be fitted during said test), a 1500N load applied vertically through the axle (to induce bending, failure for rigids if displacement is greater than 5mm), a +/- 650N vertical loading through the axle cycled (1e5 cycles), a 22.5kg striker dropped from 360mm onto the axle (if passed same test but from 600mm), a cycled braking torque (600N at 330mm from the axle, 12000 cycles) and a 330Nm torque test about the axle.

Unfortunately for some of the tests (striker and cycled tests) I do not have enough information about the forces involved to be able to calculate it correctly. In the case of the striker a safety factor of 4 has been assumed to take up any shock loading. In the terms of the cycled test I have no information about the low cycle fatigue properties of my chosen material (T45) or high cycle fatigue properties, hence safety factors have been taken into account (various depending on the specific test).

In order to make forks there are some very specific tools to cut the face for the crown race to sit on, due to how expensive these are and the lack of a shop near me that stocks the tools I opted to design the forks around the only system that I could find that would allow a pre-made crown and steerer system which would be any dual crown fork. Fig. 3 shows the crowns that I managed to buy second hand and are made for 32mm (~1.25") stanchions.

|

| Fig. 3 - 2010 Rockshox Boxxer dual crown steerer and crowns |

From the geometry given in Fig. 1 (i.e. a 120mm head tube, 510 ATC and 67.5mm fork offset) there was very little in the way of flexibility in the geometry. For the chosen material (T45, a material primarilly used for roll cages and space frame chassis, 620MPa minimum yield) there is one supplier that I would trust (as recommended by the Formula Student team) and of all the sizes they stock I am only able to use on of them, a 10SWG (3.251mm) thickness tube. This thickness was decided upon only during the frame and fork testing based on the stress and resulted in a stress of 600MPa which although would pass a single cycle did not provide a high enough factor of safety.

In order to get around the factor of safety issue without buying new crowns from a fork that uses a larger stanchion or getting custom tubing that had a thickness of 8SWG (4.064mm) I incorporated the second moment of area of the area of the steerer as well as the crowns. To get around the issue of dissimilar materials their strength was taken to be a half of its true value which will provide a accurate enough stress profile.

Another way to get around the high stress towards the crowns (which were treated as pin supports for the purposes of calculation) a tube with an outer diameter of 1-3/8" and then bored out to slide over the top of the stanchion as a lug and then brazed on. This allows for a much higher thickness where required, for a minimum lug length of 150mm (it would not be clean cut but shaped to reduce the stress risers) then provides a maximum stress of 400MPa which is a much more acceptable factor of safety for cycled loading.

Below (Fig. 4 through 11) can be seen the results of the calculations performed for the different tests. It should be noted that the steps in stress are due to a non-constant second moment of area value throughout the length of the forks. Ideally this should be taken into account throughout (for the slope and displacement), however I have decided that regardless of the displacement that the material being used is the thickest that I can purchase so there is nothing more that I can do about it. Along side this it would take me a long while longer to perform these calculations to gain a slightly higher level of accuracy.

|

| Fig. 4 - 22.5kg drop with 4G safety |

|

| Fig. 5 - 22.5kg with 4G safety |

|

| Fig. 6 - 1500N fork bending |

|

| Fig. 7 - 1500N fork bending |

|

| Fig. 8 - 1200N frame and fork bending |

|

| Fig. 9 - 1200N frame and fork bending |

|

| Fig. 10 - 330Nm Braking torque |

|

| Fig. 11 - 330Nm Braking torque |

Unfortunately, as can be seen in Fig. 6, the displacement is greater than 5mm for the 1500N test, this would mean that (if the calculations are accurate) the forks would fail type approval. However for a project such as this it is of little concern to myself as I will make sure there is ample clearance between the down tube and the wheel (by using a cranked down tube).

In addition to the calculations I have performed some basic finite element analysis, FEA, (due to only having a student license for the software) on a basic cad model of the forks. The pin supports were created by making large thin discs attached to the stanchions and then fixing the outside face of these discs to allow rotation the most free rotation whilst preventing vertical and motion as best as possible (any torque arms were applied to not create lateral reaction forces in the thin discs). Below are some images for the torque moment (330Nm) and the e-drawings files (

edrawings download here) with the deflections, stresses and factors of safety (it should also be noted that the material is similar but not identical, the yield strength in T45 is ~20% greater than that of the material chosen), in the factor of safety plots there is often a very high factor of safety around the axle, this is irrelevant due to the axle only being used during testing and not being representative of the hub assembly.

|

| Fig. 12 - Displacement in basic fork |

|

| Fig. 13 - FOS in basic fork |

|

| Fig. 14 - Stresses in basic fork |

The tests carried out, in FEA, are the 1200N frame and fork, the 1500N fork bending, 330Nm braking torque and a 660Nm braking torque. The stresses around the drop outs are not of concern as there would be radii to lower the stress concentration. Interestingly the FEA does not show a displacement of more than 5mm for the 1500N test and this discrepancy will be due to my stepped inertia values during the calculation stages (mentioned previously).

Now that I have decided upon the material, sizes, thickness's and general frame geometry I can begin to purchase components. The most important components at this stage are the wheels as they will be used to implement my dual disc system. In order to do this I am using a double fixed sealed hub with two 'dixxie' (disc fixed) adaptors for the hub instead of my previously designed hub (as it is easier to buy the components than to make my own hub costing me a lot of time) which can be seen in my previous blog post (

here). After this has been designed in the wheels can be built. In order to get enough strength for these 36 inch wheels (10 inches bigger than the standard mountain bike size) the wheels will be built into a 4x pattern by the wheel builder Mike Moore (

Mike's Bikes), this should provide ample strength in the wheel for the dual disc system and for general trail riding.

Sponsored by